Special issue of Journal of Effective Teaching.

The Journal of Effective teaching has a special issue on evolution education.

Journal of Effective Teaching

Volume 9, Issue 2, September 2009

Special Issue – Teaching Evolution in the Classroom

Full Issue – PDF

CONTENTS

Letter from the Editor-in-Chief:: Origins …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1-3

Russell L. Herman …………………………………….. HTML, PDF

ARTICLES

The Influence of Religion and High School Biology Courses on Students’ Knowledge of Evolution

When They Enter College ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4-12

Randy Moore, Sehoya Cotner, and Alex Bates ………………………. Abstract, HTML, PDF

Teaching Evolution in the Galápagos ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 13-28

Katherine E. Bruce, Jennifer E. Horan, Patricia H. Kelley, Mark Galizio ……………….. Abstract, HTML, PDF

A College Honors Seminar on Evolution and Intelligent Design: Successes and Challenges ……………………… 29-37

Patricia H. Kelley …………………………………………….. Abstract, HTML, PDF

Clearing the Highest Hurdle: Human-based Case Studies Broaden Students’ Knowledge

of Core Evolutionary Concepts …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 38-53

Alexander J. Werth ………………………………….. Abstract, HTML, PDF

Evolution in Action, a Case Study Based Advanced Biology Class at Spelman College ………………………….. 54-68

Aditi Pai ……………………………………………………. Abstract, HTML, PDF

Preparing Teachers to Prepare Students for Post-Secondary Science:

Observations From a Workshop About Evolution in the Classroom ………………………………………………….. 69-80

Caitlin M. Schrein, et al. …………………………… Abstract, HTML, PDF

My voice sounds less weird than I expected.

I did a brief radio interview with our campus station CFRU on today’s The Press Conference about our BioScience paper on graduate student understanding of evolution. Enjoy.

The Do-As-I-Say-Not-As-I-Do-Omics award.

I am the proud recipient of a “Worst New Omics Word Award” from Jonathan Eisen, who blogs at Tree of Life. Usually these go to actual ‘omics words (so far: diseasome, ethomics, and museomics). It seems he thinks “omnigenomics” to describe the study of genome sizes (i.e., all components of the genome) in all organisms (omnis = all) is in the same category. People really should not be adding prefixes to “genomics”, according to Dr. Eisen. Right?…

phylogenomics.blogspot.com

Eisen JA and Fraser CM. Phylogenomics: intersection of evolution and genomics. Science 2003 Jun 13; 300(5626) 1706-7.

Eisen JA. Gastrogenomics1. Nature 2001 Jan 25; 409(6819) 463, 465-6

Eisen JA. Environmental shotgun sequencing: its potential and challenges for studying the hidden world of microbes. PLoS Biol 2007 Mar; 5(3) e82.

“A review I wrote on methods for characterizing uncultured microbes, focusing on the lead in to metagenomics.”

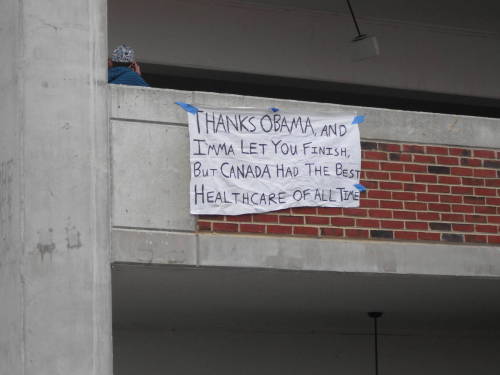

Laughter IS the best medicine, right?

How well do grad students grasp evolution?

In my recent article on Understanding natural selection in E:EO, I reviewed a large number of studies that examined conceptions of evolution among students from the high school to undergraduate level, as well as among teachers. However, almost nothing seemed to be known about how graduate students in science perceive evolution or how well they understand it. At least, until a student and I did a study at our own university, which is now out in the journal BioScience.

Here’s a press release on it:

Science Students Could Brush Up On Darwin, U of G Study Finds

October 01, 2009 – News Release

Even students pursuing advanced degrees in science could brush up on their knowledge of evolution, according to a new study by University of Guelph researchers.

The finding reveals that there is room for improvement in how evolution is taught from elementary school up, said Ryan Gregory, a professor in Guelph’s Department of Integrative Biology, who conducted the research with former student Cameron Ellis.

The study was published today in BioScience. It’s particularly timely, given that this year is the bicentennial of Charles Darwin’s birth and the 150th anniversary of publication of On the Origin of Species, which underpins understanding of the diversity of Earth’s organisms and their interrelations.

“Misconceptions about natural selection may still exist, even at the most advanced level,†Gregory said.

“We’re looking at a subset of people who have spent at least four years, sometimes even six or seven years, in science and still don’t necessarily have a full working understanding of basic evolutionary principles or scientific terms like ‘theories.’â€

Many previous studies have assessed how evolution is understood and accepted by elementary, high school and undergraduate students, as well as by teachers and the general public, Gregory said. But this was the first to focus solely on students seeking graduate science degrees.

The study involved nearly 200 graduate students at a mid-sized Canadian university who were studying biological, physical, agricultural or animal sciences. About half of the students had never taken an evolutionary biology course, which is often not a prerequisite.

The researchers found that the vast majority of the students recognized the importance of evolution as a central part of biology. Overall, they also had a better understanding of evolutionary concepts than most people.

“That was encouraging, especially because it was across several colleges — it wasn’t just the biology students,†Gregory said.

But when the students were asked to apply basic evolutionary principles, only 20 to 30 per cent could do so correctly, and many didn’t even try to answer such questions. Of particular interest to Gregory is the finding that many students seem less than clear about the nature of scientific theories.

“This is telling us that traditional instruction methods, while leading to some basic understanding of evolution, are not producing a strong working knowledge that can be easily applied to real biological phenomena.â€

Gregory has studied evolution-related topics for years and recently co-organized a workshop designed to improve how the subject is taught in public schools. He is also associate editor of Evolution: Education and Outreach, a journal written for science teachers, students and scientists. He recently created Evolver Zone, a free online resource for anyone interested in evolutionary biology.

He is also helping bring an evolution-inspired art exhibit to U of G this month. “This View of Life: Evolutionary Art in the Year of Darwin, 2009†highlights diverse artists’ views of Darwin’s ideas and evolution in general. It runs Oct. 9 to 30 in the science complex atrium.

Overall, the students did well on multiple choice questions, and their acceptance of evolution was very high. But it seems we could do a better job at providing students with the capability to actually use evolutionary concepts to explain phenomena.

Humans vs. chimps — neither is an offshoot.

Tomorrow’s Science will be a special issue reporting tons of new information on the fossil hominid Ardipithecus ramidus (“Ardi”), which is really exciting (though not as much as Darwinius, which was “like a meteor hitting the Earth” or whatever).

Tomorrow’s Science will be a special issue reporting tons of new information on the fossil hominid Ardipithecus ramidus (“Ardi”), which is really exciting (though not as much as Darwinius, which was “like a meteor hitting the Earth” or whatever).

There are news reports of course, including one at USA Today that I want to comment on briefly:

The analysis of Ardipithecus ramidus (it means “root of the ground ape”), reported in the journal Science, changes the notion that humans and chimps, our closest genetic cousins, both trace their lineage to a creature that was more like today’s chimp. Rather, the research suggests that their common ancestor was a walking forest forager more cooperative in nature than the competitive, aggressive chimp…

[So far, so good, but then…]

…and that chimps were an evolutionary offshoot of this creature.

Nope. Neither humans nor chimps are offshoots of this creature, they are (if the phylogenetic assumption is correct) both descendants of a creature similar to this (but probably not this one per se). Otherwise it’s like arguing that your cousin is an offshoot of your grandmother and you’re not.

Luckily, one of the authors is quoted as giving a more reasonable interpretation:

So that could mean that while humans didn’t diverge much from their evolutionary ancestors, “chimps and gorillas look like really special evolutionary outcomes,” says Science study author Owen Lovejoy of Ohio’s Kent State University.

Right. This would make many of the obvious traits of chimps derived rather than primitive, and many classically human traits primitive rather than derived. (It doesn’t really matter in one sense, because every species is a mixture of primitive and derived traits, but it sure would destroy those evolutionary lineups with chimps at one end and humans at the other).

Much to no one’s surprise, Carl Zimmer presents a good story on the topic:

Chimpanzees may be our closest living relatives, but that doesn’t mean that our common ancestor with them looked precisely like a chimp. In fact, a lot of what makes a chimpanzee a chimpanzee evolved after our two lineages split roughly 7 million years ago. Ardipithecus offers strong evidence for the newness of chimps.

Only after our ancestors branched off from chimpanzees, Lovejoy and his colleagues argue, did chimpanzee arms evolve the right shape for swinging through trees. Chimpanzee arms are also adapted for knuckle-walking, while Ardipithecus didn’t have the right anatomy to lean comfortably on their hands. Chimpanzees also have peculiar adaptations in their feet that make them particularly adept in trees. For example, they’re missing a bone found in monkeys and humans, which helps to stiffen our feet. The lack of this bone makes chimpanzee feet even more flexible in trees, but it also makes them worse at walking on the ground. Ardipithecus had that same foot bone we have. This pattern suggests that chimpanzees lost the bone after their split with our ancestors, becoming even better at tree-climbing.

Chimpanzees do still tell us certain things about our ancestry. Our ancestors had chimp-sized brains. They were hairy like chimps and other apes. And like chimps, they didn’t wear jewelry or play the trumpet.

But then again, humans turn out to be a good stand-in for the ancestors of chimpanzees in some ways–now that Ardipithecus has clambered finally into view.

See also:

- ScienceNOW (and watch the video)

- Anthropology.net

- Why Evolution is True

What do you think of when you hear the word science?

Interesting brief post by Kiki Sanford on the results of word association analyses using the term “science”. Here is a Wordle cloud showing the responses of 126 people when asked what comes to mind when they hear the word “science” (larger = more common).

Dunno about you, but I get pretty tired of (some) physicists and philosophers equating science with physics, and how to do science with how physicists do it. Biology is where it’s at in this century, man, and we do things a little differently (but not less rigourously) in the life sciences. Interesting that public perception is starting to catch this message too, at least in the sample highlighted above.

CSI: Common Scientific Illiteracy.

I don’t watch CSI. Ok, that’s not totally true or this post wouldn’t exist. I almost never watch it. I did catch a re-run while I was eating lunch on the weekend, an episode called “Overload” (some guy was electrocuted and fell off a building — I can’t exactly remember why).

In one scene, the lead character says, in what I assume is his typical “know it all” tone, “Terminal velocity is 9.81 metres per second per second”.

No, it ain’t — the acceleration due to gravity (on Earth) is 9.81 m/s2. The second time unit gives it away — this isn’t a velocity, it is a rate of change of a velocity.

So what?

Well, any kid in high school physics could have picked out that error. But here we have a screenwriter (probably a team of them), a director, producers, all the actors, sound techs, cameramen, editors, and post-production people involved in the scene, and evidently not one of them knows even the most basic physics concepts. More seriously, the producers of the show must assume that it doesn’t matter whether basic facts are checked because the audience is likely similarly uninformed. This really isn’t artistic license, and it adds nothing to the drama. It’s just a goofy mistake that could have been prevented — as Carl Sagan recommended in The Demon-Haunted World — by hiring a grad student to check the script.

Nitpicking? Maybe. But I think it’s a sad situation when no one involved in a science-themed show is even qualified to nitpick.

Omnigenomics.

Sometimes it is helpful to have a catchy word to describe one’s type of research. I think that’s why “omics” words are so popular — they encapsulate a complex combination of approaches (usually something + genomics, or something-more-than-genomics) in a memorable way that immediately conveys the gist of the field. “Metagenomics” is a good example — it’s the study of a larger assemblage of genomes than just one, usually from an environmental sample of microbes. “Proteiomics” is another, or “transcriptomics”. Of course, this can get out of hand (see here). However, I think the study of genome size (which predates molecular genetics, let alone genomics) deserves a catchy moniker. The problem is, I haven’t really come up with one in the past, so I just end up saying “I study the total amount of DNA in different species of animals, which includes genes and all the other sequences, most of which are non-coding and…” — well, you get the idea.

Sometimes it is helpful to have a catchy word to describe one’s type of research. I think that’s why “omics” words are so popular — they encapsulate a complex combination of approaches (usually something + genomics, or something-more-than-genomics) in a memorable way that immediately conveys the gist of the field. “Metagenomics” is a good example — it’s the study of a larger assemblage of genomes than just one, usually from an environmental sample of microbes. “Proteiomics” is another, or “transcriptomics”. Of course, this can get out of hand (see here). However, I think the study of genome size (which predates molecular genetics, let alone genomics) deserves a catchy moniker. The problem is, I haven’t really come up with one in the past, so I just end up saying “I study the total amount of DNA in different species of animals, which includes genes and all the other sequences, most of which are non-coding and…” — well, you get the idea.

People like me study entire genomes — every component included, be it gene or pseudogene or repeat or transposable element. We also are interested, not in a few model organisms, but in everything (people usually stare blankly when, to the question “which animals do you work on?”, I reply “all of them”). But what to call such a discipline?

Proposed neologism: “Omnigenomics”

Etymology: Latin “omnis” (all or everything) + genomics (study of genomes)

Sample usage: “What do you do?” / “Omnigenomics” / “What’s that?” / “I study the total amount of DNA in different species of animals, which includes genes and all the other sequences, most of which are non-coding and…”

(The alternative Greek version, “pangenomics”, is already being used and sounds way less cool).

(Yes, I note the irony of getting a “worst new omics word award” from a blog called phylogenomics.blogspot.com!)