The primary goal of a magazine is to sell magazines. However, if a magazine is about science and wishes to preserve its credibility as a source of science information (and thus, to sell magazines), it should do its best to avoid unnecessary hype, especially when this touches on sensitive issues in science policy or education.

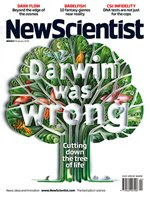

Well, I am afraid to say that New Scientist, which I have previously praised for excellent, balanced coverage [here and here], now looks to be taking the hype road.

Look at these two recent cover stories.

Forget genes? Really? This story was about epigenetics, and floated the idea that maybe evolution is Lamarckian after all. Nevermind the fact that they don’t seem to know what Lamarckian evolution actually is.

This one has, rightly, provoked the ire of many bloggers/scientists [see here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here]. It is without question irresponsible, poorly timed, and sure to be invoked by anti-evolutionists, making the job of defending science and science education more difficult. The explanation offered by the author/editor for it is unacceptable.

Fundamentally, Darwin was right about his two big ideas that really matter: common descent and natural selection. To say “Darwin was wrong”, even within the article’s context, is nonsense. The fact that it will undoubtedly be taken to refer to the big ideas rather than a specific analogy makes it infuriatingly misleading.

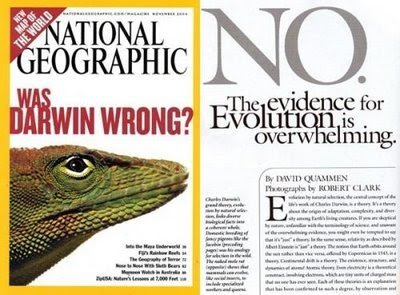

Compare this with the approach taken by National Geographic.

Pretty provocative cover, but still phrased as a question — and answered without ambiguity.

There is a lot that Darwin didn’t know, and I hope that the success of evolutionary biology in the 150 years since the Origin is talked about in abundance this year. But the fact that his two big ideas, common descent and natural selection, have survived every scientific discovery since the mid 1800s is overwhelmingly convincing that he was brilliant and insightful and right. (The associated story, Modern Darwins by Matt Ridley, is certainly worth reading.)

To be clear, I don’t think magazines should make decisions about their covers or articles solely on the basis of how anti-evolutionists might use them. But as communicators, they — and any scientists interviewed in popular articles — have a responsiblity to think about the implications of what they say.

As pointed out recently by Scott and Branch,

in science, we do not shape our research because of what creationists claim about our subject matter. But when we are in the classroom or otherwise dealing with the public understanding of science, it is entirely appropriate to consider whether what we say may be misunderstood.

I strongly encourage New Scientist to rethink the message that cover stories like this send.