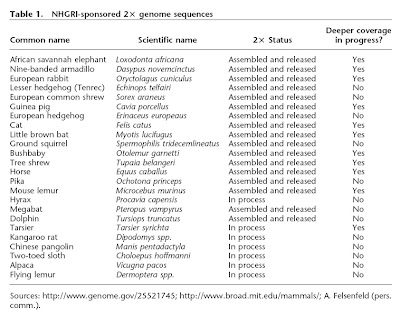

The most recent issue of Genome Research contains a report of the cat genome sequence (Pontius et al. 2007), adding Felis catus to the rapidly growing collection of animal genome sequences. One of the reasons that the number of mammal sequences is increasing so quickly is that there have been reduced standards for sequence coverage. To wit, the cat is one of 24 mammal species approved by NHGRI for “low redundancy” sequencing, meaning that the sequence will be covered only 2-fold (vs. up to 7x coverage in dog, chimp, human, mouse, and rat). Moreover, in this report, only 60% of the euchromatic DNA was actually sequenced (and nevermind the heterochromatin). Seventeen of these low redundancy genomes have already been released, as noted in the table from Green (2007). This leaves many gaps in the sequence, but the rationale is that having incomplete genomes from many species can be at least as informative as having more thorough sequences from only a few species.

In the trade-off between breadth vs. depth — or phylogenetic diversity vs. individual resolution — this leans more towards the former. Of course, this does not preclude improving coverage later, and in fact many of the 2x genomes are already being sequenced to a higher redundancy.

http://www.genome.org/cgi/content/short/17/11/1547

http://www.genome.org/cgi/content/short/17/11/1547

Speaking of the dog genome, it bears noting that a survey sequence of only about 25% of the genome at 1.5x coverage was released in 2003 (Kirkness et al. 2003). This initial sequence (from Craig Venter’s poodle Shadow) was followed by work from a different set of authors who released a complete dog genome (7.5x coverage) in 2005 (Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005). So again, releasing a partial sequence certainly does not stop a more detailed coverage from being done down the line.

In an ideal world we might have high redundancy, totally complete (not just euchromatic), fully annotated, completely accurate genome sequences from multiple individuals from thousands of species — but that isn’t reality for the time being.

Given such constraints, do you think we should have incomplete data from lots of species, or high depth information from a few species? In other words, are you a cat genome person or a dog genome person?

http://www.genome.gov/Images/feature_images/dog_image.jpg

_________

ps: You’ll note that I resisted the temptation to post pictures of my own cats — you’re welcome.