Over at Aetiology, Tara Smith has posted an excellent video comprised of interviews of science bloggers conducted at the ASM meeting in Toronto. I am not a microbiologist, but Larry Moran did kindly invite me to join the group for dinner during the meeting. Alas, I was in Montreal at the CSZ meeting presenting the Boutilier Lecture and was unable to attend. I also did not make it to the SMBE meeting in Halifax, which has been a source of consternation for RPM. Next time! It’s a very good video, although I felt like Jonathan Badger really phoned it in (ha ha).

Acceptance of evolution in Canada.

There seems to be some confusion regarding the level of acceptance of evolution in Canada based on the Angus Reid poll in June 2007. In particular, several people have made the claim that the level of acceptance of this unifying principle of biology is roughly the same in Canada as in the United States. Although the results of the AR poll are disappointing, they do not indicate an equivalence of views between the two nations.

Here are two relevant press releases from Angus Reid:

U.S. Majority Picks Creationism over Evolution (April 25, 2006)

Most Canadians Pick Evolution Over Creationism (June 19, 2007)

It is true that the recent poll suggests that nationally, a disappointingly low majority of 59% of Canadians accept the notion of common descent. However, only 22% accept young earth creationism. In Ontario, the data are especially disheartening, with only 51% of respondents accepting evolution (but still only half as many choosing creationism). In Quebec, 71% accept evolution and only 9% align with creationist ideas. The original report can be accessed here.

The US poll referred to above (by CBS) indicates that 53% of respondents believe that life was created in its current form within the past 10,000 years by God, 23% accept a form of evolution guided by God, and 17% believe in a strictly natural evolutionary account. The questions in the Canadian poll were not broken down in this way, but this poll still indicates that only 40% of Americans accept any form of evolution and 53% believe in a young earth. Other polls give similar results (see Miller et al. 2006, Science 313: 765-766). There is, unsurprisingly, a strong relationship between religiosity, political affiliation, and opinion about evolutionary science.

A more recently conducted Gallup poll gave slightly more promising results than the earlier CBS finding, with 43% choosing young earth creationism, 38% ascribing to theistic evolution, and 14% accepting unguided evolution. This would put the total who accept some form of evolution at 52%, and when asked directly about evolution, 53% of respondents considered it to be either “definitely true” (18%) or “probably true” (35%). However, this encouraging result must be weighed against the fact that when asked directly about young earth creationism, 66% said it was either “definitely true” (39%) or “probably true” (27%). As Gallup put it,

It might seem contradictory to believe that humans were created in their present form at one time within the past 10,000 years and at the same time believe that humans developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life. But, based on an analysis of the two side-by-side questions asked this month about evolution and creationism, it appears that a substantial number of Americans hold these conflicting views.

Clearly, Canada does not rank at the level of nations like Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, France, or Japan where public acceptance of evolution is very high (up to 80%), but neither do they fall in the same category as the United States. In particular, what we do not see in Canada, at least based on this single survey, is a high level of acceptance of creationism. Nevertheless, there is much work to do in educating the public in Canada. Most notably, an alarming percentage (42%) believe that humans and dinosaurs coexisted despite a majority accepting evolution. In other words, they are right about evolution but rather confused about the details of life’s history. In some ways, this is not surprising, given the countless portrayals of “cavemen” and dinosaurs together in cartoons, movies, and other venues. I would not be surprised if a majority of people also believe that penguins and polar bears cohabitate while accepting the fact of a round Earth with two poles.

On framing.

I finally checked out the “framing” presentation by Chris Mooney and Matthew Nisbet which is available with PowerPoint slides here. I am not particularly interested in the debate over this issue, but I thought I would give it a try in light of my hope of improving media coverage and public comprehension of science. This is not my entry into the debate as I think it has garnered more attention that it warrants already; this is simply a set of thoughts on the issue after having spent the time watching the talk.

I will say that I found much to agree with as far as the descriptive components were concerned. That is, I think Mooney and Nisbet make some good arguments with regard to what is and is not working in scientific communication. This is Nisbet’s subject of research, and it was useful to see actual data applied to the question. My sense was that “framing” likely is something that nonspecialists do use when evaluating complex issues, and that this is a problem for scientists who want to convey complicated ideas with societal ramifications to them. However, I think the discussion runs aground in three major areas: 1) How it is presented to scientists, 2) In the failure to distinguish it from “spin” or “marketing”, and 3) When it shifts from description to prescription.

As to the first, Mooney and Nisbet seem to use an only partially appropriate “framing” when speaking to scientists who, both as individual people and as part of a collective, exhibit inherent preferences, biases, and other filters. To wit, scientists in general will be unwilling to compromise certain principles, and there appears to be insufficient appreciation of this fact by framing advocates. For example, scientists will not simplify to the point of eroding accuracy, they will not do anything that could be perceived as lying to the public, and they will never give up on the notion that getting the public to understand science is the primary long-term goal. From what I can gather, Mooney and Nisbet are not asking scientists to compromise on these principles, but this is not stated clearly — following their own advice, this should be presented clearly and repeatedly so as to reassure scientists that they are not being told to betray their scientific ideals. (And if they are asking scientists to do so, then this should be made clear also so that the debate can be put to a swift end).

The question of motives also comes into play as part of the mis-framing of framing. No one can be totally objective, so what scientists are trained to do is to look for biases and associated violations of objectivity so that these can be factored into the evaluation of scientific arguments. Personally, I found myself asking “why do they care what scientists do?”. One obvious explanation is that they are concerned citizens with a particular interest in science and its impacts on society. This is not stated upfront, however, and so questions come up about whether this isn’t an exercise in attention getting (and possibly book promoting) as much as a sincere call to action.

Finally, while I do not read their blogs, I have seen a few links to statements that I have found offensive to my scientific sensibilities. As a case in point, Mooney argues on his blog that science journalists are not the problem (this is also stated in the presentation). It would seem to follow, therefore, that if science is reported inaccurately, sensationalized, overstated in its implications, or otherwise distorted, that is the fault of scientists. Worse, Mooney goes so far as to argue that scientists should just shrug it off and move on if they are misquoted in the media. Again, this ignores the frame that scientists use, in which accuracy is of paramount significance. He also seems to think that simply telling scientists about the difference between a science journalist (well-trained and comprehensive) and a non-science journalist reporting on science (no expertise or experience in dealing with such issues) will make the resentment of the media’s handling of research disappear. It will not.

The second point is the one that has been the primary subject of discussion by some prominent scientist-bloggers, namely that “framing” bears a striking resemblance to “spin”. We all know that “spin” plays a substantial role in politics. To scientists, this is not something to be emulated. I won’t go so far as to say that framing is mere spin, but throughout the presentation I had the strong notion that it was largely indistinguishable from “marketing”. Scientists should care about how their work is presented to and received by the public, and therefore marketing is a legitimate consideration. Indeed, scientists market their work often — to granting agencies, students, journals, and colleagues. Adding some audience-specific adjustments when dealing with the public is perfectly reasonable, but if that’s all “framing” is, then it’s really just repackaged marketing truisms.

The third point, in which Mooney and Nisbet transition from describing the issue to prescribing what scientists should do, was by far the weakest part of the talk. In fact, I found almost nothing in their presentation that actually applied to me as an individual researcher. Almost everything they suggested actually fell under the purview of science writers, press offices, lobby groups, professional societies, or educational organizations. I still do not know what they expect me to do even with information in mind about how the public frames important topics. As a result, much of the talk seems to be about telling scientists what they are doing wrong with no real solutions that individual scientists can or will implement.

If I may, I would also add that Mooney and Nisbet’s discussion is, at heart, not about science or communication, but about American politics. In many other countries, scientific literacy is much higher, issues do occupy the primary stage in election campaigns, and religion and partisanship play a much smaller role in influencing decisions about science. Once again, this suggests that education about science early on is an effective strategy and a viable objective. The question of framing is more geographically and temporally localized than this, and so it is difficult for some scientists who are trained to look beyond such limitations to the larger picture to make framing a primary tool.

In stark contrast to all of this ambiguity and apparent misreading of scientific audiences, I point to the recent book A Scientist’s Guide to Talking with the Media by journalists Richard Hayes and Daniel Grossman, published by the Union of Concerned Scientists. I am only part way through the book, but already I can note that it does a fine job of framing the topic in a manner acceptable to scientists. Hayes and Grossman are very clear that they have the utmost respect for science and scientists, and that they absolutely do not wish to see spin implemented at the expense of accuracy. Theirs is a well articulated set of practical suggestions for dealing with the media. They do not appear to blame scientists but instead point to examples where different strategies could have forestalled problems. They do not let science reporters off the hook, but do try to promote a better understanding among scientists of the challenges of writing for a nonspecialist audience. They do not point out the challenge and leave the solutions unclear, but give point by point suggestions on how to improve the important relationship between scientists and those who report science. As a scientist with some experience with the media, I find a great deal of use in this volume. And I do not hesitate to recommend it as an alternative to the far less helpful argument about framing.

In stark contrast to all of this ambiguity and apparent misreading of scientific audiences, I point to the recent book A Scientist’s Guide to Talking with the Media by journalists Richard Hayes and Daniel Grossman, published by the Union of Concerned Scientists. I am only part way through the book, but already I can note that it does a fine job of framing the topic in a manner acceptable to scientists. Hayes and Grossman are very clear that they have the utmost respect for science and scientists, and that they absolutely do not wish to see spin implemented at the expense of accuracy. Theirs is a well articulated set of practical suggestions for dealing with the media. They do not appear to blame scientists but instead point to examples where different strategies could have forestalled problems. They do not let science reporters off the hook, but do try to promote a better understanding among scientists of the challenges of writing for a nonspecialist audience. They do not point out the challenge and leave the solutions unclear, but give point by point suggestions on how to improve the important relationship between scientists and those who report science. As a scientist with some experience with the media, I find a great deal of use in this volume. And I do not hesitate to recommend it as an alternative to the far less helpful argument about framing.

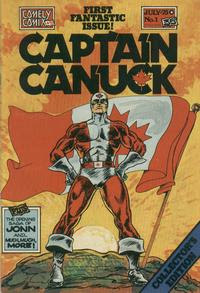

Gene Genie #10 — The Canada Day Ultraspectacular Edition.

Gene Genie was the brainchild of Bertalan Meskó of ScienceRoll. At bi-weekly intervals since February 17, 2007, it has provided a showcase of blogging on the subject of genetics, and has moved well beyond its initial tongue-in-cheek “objective” of covering every gene in the human genome by 2082. In light of its effectiveness in sharing the excitement of discovery in genetics, it is hardly surprising that Gene Genie was mentioned, along with Mendel’s Garden, in a recent issue of the prestigious journal Cell. It was also an easy decision to commit to hosting an issue here at Genomicron when I was asked to do so. It is perhaps fitting (albeit mostly coincidental) that the 10th issue of Gene Genie, which I was invited to host, falls on July 1st — Canada‘s 140th birthday. And so, it is with typical Canuck modesty that I am pleased to present the Canada Day Ultraspectacular Edition of Gene Genie.

surprising that Gene Genie was mentioned, along with Mendel’s Garden, in a recent issue of the prestigious journal Cell. It was also an easy decision to commit to hosting an issue here at Genomicron when I was asked to do so. It is perhaps fitting (albeit mostly coincidental) that the 10th issue of Gene Genie, which I was invited to host, falls on July 1st — Canada‘s 140th birthday. And so, it is with typical Canuck modesty that I am pleased to present the Canada Day Ultraspectacular Edition of Gene Genie.

We begin with a classic in the truest sense of the term. As the June 22nd entry for his weekly series on citation classics, John Dennehy of The Evilutionary Biologist discusses the famous Hershey-Chase “blender experiment” in 1952 that helped to establish the role of DNA in inheritance. The details of the relationship between DNA sequence and phenotype are, of course, still being elucidated 55 years later.

Case in point, discussion continues about the results of the pilot study of the ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) project (for previous links, see here and here). Indeed, it appears that the very definition of “gene” is open to revision. Larry Moran of Sandwalk and adaptivecomplexity of Scientific Blogging discuss a paper by Gerstein et al. in Genome Research that summarizes the history of the gene concept and offers a new definition.

Scientific Blogging has a follow-up on the implications of ENCODE data. Along the same lines, Nick Matzke at Panda’s Thumb has re-posted my “onion test” in the hope of mitigating some of the undue enthusiasm about function for “junk DNA”. (To clarify, the test is neither anthropocentric nor onionocentric — it is just a useful comparison). And speaking of hype about genomes, Jonathan Eisen at The Tree of Life has instituted the “Overselling Genomics Awards“. I suspect that nominees will not be scarce.

Questions about definition aside, several recent blog entries have explored how genes are structured, how they do what they do, and how they evolve. Thus, Larry Moran discusses RNA splicing and the Nobel Prize winners, Richard Roberts and Phillip Sharp, who first identified the intron-exon structure of eukaryotic genes. PZ Myers of Pharyngula gives an overview of pair-rule genes and Evolution Research Blog provides a discussion of genomic imprinting in mammals. RPM at Evolgen examines the causes of variation in the rate of molecular evolution and the genetic underpinnings of smell and taste in Drosophila (which, incidentally, are not fruit flies). Evolution Research News discusses the link between genes and intelligence; environment also matters, of course, especially given new work suggesting that not just birth order but being raised as the eldest affects IQ. Remember: nature versus nurture is a false dichotomy.

Next, VWXYNot? provides a very good overview of the evolutionary explanatio n for endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), be they functional or not. ERV (the person, not a DNA element) introduces us to the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV), which exhibits both endogenous and exogenous viral properties. ERV also discusses her HIV research and Carl Zimmer of The Loom describes one possible reason that humans are susceptible to HIV, having to do with a previously evolved defence against an ERV (a DNA element, not the person). This Week in Evolution also delivers an overview of this interesting trade-off. Meanwhile, Denialism Blog and Aetiology highlight a report in Science about AIDSTruth.org, the electronic antidote to AIDS denialism.

n for endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), be they functional or not. ERV (the person, not a DNA element) introduces us to the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV), which exhibits both endogenous and exogenous viral properties. ERV also discusses her HIV research and Carl Zimmer of The Loom describes one possible reason that humans are susceptible to HIV, having to do with a previously evolved defence against an ERV (a DNA element, not the person). This Week in Evolution also delivers an overview of this interesting trade-off. Meanwhile, Denialism Blog and Aetiology highlight a report in Science about AIDSTruth.org, the electronic antidote to AIDS denialism.

As usual, medical and other applications of genetics featured prominently in the scientific blogosphere in the past two weeks. Notably, Hsien-Hsien Lei at Eye on DNA discusses BRCA genetic testing for women without a family history of breast cancer. Over at Autism Vox there is a report about symptoms of fragile X being reversed in mice. FuturePundit notes how gene therapy may halt Parkinson’s disease. Both Eye on DNA and Dr. Joan Bushwell’s Chimpanzee Refuge weigh in on the association between genetics, the environment, and behaviour, in particular with respect to the monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene and susceptibility to alcoholism. Gene Sherpas continues the series on Forbes and Genetics, this time discussing smoking and obesity. And I do some reflecting on my possible ancestry, which could be established with a simple DNA test, in Am I a MacGregor? here at Genomicron.

And finally, under the category of edutainment, Discovering Biology in a Digital World shares a  link to some excellent animations of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that is now ubiquitous in molecular genetics, The Genetic Genealogist reports on the creation of a bicycle path in Cambridge in honour of the discovery of the BRCA2 gene, mutations of which are implicated in increased risk of breast cancer, and Bertalan Meskó at ScienceRoll interviews the creator of the Genomic Island in the popular online 3D virtual environment of Second Life. He has also posted a more detailed discussion about educational aspects of the online world here.

link to some excellent animations of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that is now ubiquitous in molecular genetics, The Genetic Genealogist reports on the creation of a bicycle path in Cambridge in honour of the discovery of the BRCA2 gene, mutations of which are implicated in increased risk of breast cancer, and Bertalan Meskó at ScienceRoll interviews the creator of the Genomic Island in the popular online 3D virtual environment of Second Life. He has also posted a more detailed discussion about educational aspects of the online world here.

The next edition of Gene Genie will be hosted at My Biotech Life July 29th. Mendel’s Garden #16 will be hosted at Eye On DNA July 8th.

Evolution for Everyone — David Sloan Wilson on CBC.

David Sloan Wilson is Distinguished Professor of Biology and Anthropology at Binghamton University in New York and author of Unto Others, Darwin’s Cathedral, and most recently Evolution for Everyone. I confess that I have not yet read the book, though it is near the top of my pile. (Dr. Wilson and I are on the editorial board of Evolution: Education and Outreach, and he was kind enough to have copies sent to all of us).

David Sloan Wilson is Distinguished Professor of Biology and Anthropology at Binghamton University in New York and author of Unto Others, Darwin’s Cathedral, and most recently Evolution for Everyone. I confess that I have not yet read the book, though it is near the top of my pile. (Dr. Wilson and I are on the editorial board of Evolution: Education and Outreach, and he was kind enough to have copies sent to all of us).

On Saturday I happened to be listening to the radio and caught an interview with Dr. Wilson on CBC’s Quirks and Quarks program. You can listen here to a discussion of the book and his ideas about evolution, morality, religion, and other subjects. (Another connection: the host, Bob McDonald, received an honourary Doctor of Letters degree from the University of Guelph at the same convocation at which I received my degree).

Enjoy.

Collins and me, again.

Those who read the Wired piece on junk DNA and anti-evolutionism will have noticed that both Francis Collins and I made an appearance (see here for more). It’s pretty clear that our views on genome evolution differ considerably, stemming perhaps from our larger views about how evolution works (see here). It then occurred to me that this is the second time our thoughts on genomes have been juxtaposed recently. The first was in a series of book reviews in Lab Times by Weanée Kimblewood. You can read the reviews here. It seems The Evolution of the Genome was well received; The Language of God, not so much. Of course, Collins’s book ranks #583 on Amazon.com; mine, not so much.

RSS feeds: not just for blogs.

RSS, or Really Simple Syndication, is a system that allows readers to receive “feeds” of new content from various online sources to their computer without having to visit each site individually. By using an aggregator, one can subscribe to his or her favourite blogs, news feeds, and other sources of syndicated information and receive new articles as soon as they are posted online.

An amusing introduction to aggregators is given in this short video by Commoncraft:

[Hat tip: Retrospectacle via Sandwalk]

Generally speaking, subscribing to a blog or science news site is as simple as clicking on the “RSS”, “XML”, “Atom”, or other “Subscribe” link. For example, you will notice to the right some links that allow you to subscribe to the Feedburner feeds for this blog, either by email or to an aggregator, or through the larger DNA Network feed encompassing the posts of multiple genetics blogs. (The only downside for bloggers is that hits do not register if someone reads a post in a feed reader rather than coming to the blog — but hey, they’re reading the post, which is what counts!)

Aggregators can be used for more than just reading news and blogs. Many journals have their tables of contents available as RSS feeds. In addition, you can have scientific literature databases such as PubMed (which is free) and Web of Science (subscription required) automatically perform regular searches and send the results to your aggregator. This latter application is incredibly useful, but it is more complicated than subscribing to blogs or news feeds. Fortunately, the University of California San Diego has been kind enough to provide an illustrated guideline to setting up RSS feeds for these and other literature databases.

A list of client-based and web-based aggregators is available in Wikipedia. Prominent examples include Google Reader, Bloglines, and Netvibes.

Happy reading.

Flagellum discussion update.

Readers may recall the brief but intense discussion regarding the Liu and Ochman paper about bacterial flagellum evolution. As it happens, there is an update in the most recent issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), which Nick Matzke discusses critically but insightfully at Panda’s Thumb. Keep an eye out for other papers on this interesting subject.

Nonsense from home.

I grew up in and around the small city of Orillia, Ontario. It is a charming place, and was both the hometown of Gordon Lightfoot and the summer home of Stephen Leacock, in the latter case serving as the inspiration for his Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town.

My parents (both since re-married) still live in the area, and I try to get home when I can as a good son should. They also make sure that I am kept up to date with local news of interest, which mostly means stories about the hospital administration’s shenanigans (my mother is a nurse and her husband is an MD, both recently retired and glad of it) and the amazing community project for Zambia that my father and stepmother are hard at work planning.

In addition, my mother enjoys sending me things like the following letter, which appeared in one of the local newspapers. This is, I think, the third rant by a creationist that I have seen in print from this or the smaller paper. A previous one claimed that no one had ever considered the evolution of plants, and thus that creationism must be accurate. I have many botanist colleagues who would be surprised to learn of this omission. In light of the recent poll results that show only 51% of Ontarians accept evolution, I think it is informative. This, by the way, is a lower total than for the USA as a whole, which I find disconcerting. To be fair, the results would probably depend heavily on which part of the province they sampled. Rural areas and small towns differ considerably from the larger cities in various socio-political attitudes. Frankly, I don’t have the time or energy to correct the factual errors and logical fallacies in this latest letter, so I will just post it for your enjoyment (original source).

Evolutionists have their heads in the sand

Orillia Packet & Times

Editorial – Wednesday, May 23, 2007 @ 09:00Letter to the editor:

Re: M. Brown’s letter “Atheism; a sensible alternative to some”

Atheism: the belief that there is no God. Mr. Albert Einstein, the great theoretical physicist, upon having been asked how much he knew about what there is to be known, said he thought he might know about one hundredth of one per cent without doubt. Most of us know less than he did. All of which leads one to wonder how a person can come to conclude that “there is no God, no creator, no higher intelligence,” when we realize how little we know about anything in general, and origins and beginnings in particular.Atheism does not seem very sensible.

To deny evolution, Mr. Brown writes, is like putting one’s head in the sand, and to dismiss it because we still have apes, is ignorant. Well, where is the evidence for the theory? Where are all the in-between transitional life forms that Mr. Darwin and his followers were sure to be found in the fossil record? After all the digging and searching of the last 150 years, out of hundreds of thousands of fossil discoveries, there is not one clear-cut sample, when there should have been thousands. Dr. Colin Patterson, an evolutionist who was senior paleontologist at the prestigious British Museum of National History and a world-renowned fossil expert, wrote the following about his book entitled “Evolution:” “I fully agree with comments on the lack of direct illustration of evolutionary transitions. If I knew of any, fossil or living, I would certainly have included them. I will lay it on the line; there is not one such fossil for which one could make a watertight argument.”

Surely, this leads open, honest minds to conclude that the theory of evolution and all the resulting evo-babble is unproven, unsubstantiated, without evidence and just plain wrong. As a matter of fact, the earliest fossil record shows that plants and animals appeared suddenly and fully formed, much as we see them today, in complete agreement with the Biblical record. So who, in reality, is putting their head in the sand and ignoring the evidence?

All of which makes one wonder, why evolution is still being taught in our schools, and creation ignored. Why do we so readily allow our children to be misled?

P. Visser

The old saying is not quite accurate: you can go home again, just try not to read the letters to the editor in the local newspaper.

Tangled Bank #82.

The latest issue of the blog carnival Tangled Bank is available in very well crafted and entertaining form at Greg Laden‘s blog. Enjoy.