I am not planning any official blogging of the Origin (cf. Blogging the Origin), but I am currently reading it with a few students from my evolution course just for fun. We’re discussing it online and will be meeting to talk about it every week or two. I’m posting below what I posted in our discussion forum.

Chapter 1 – Variation Under Domestication

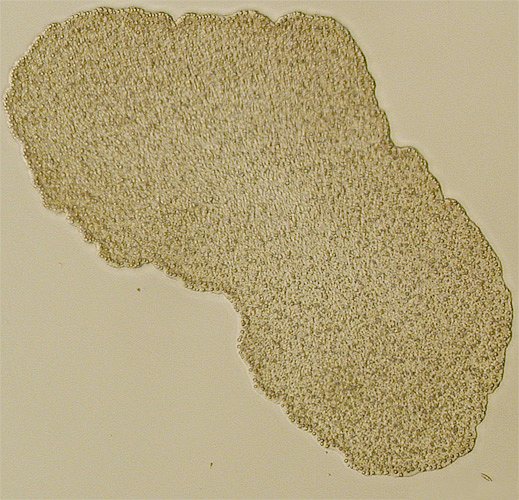

Darwin spends a lot of time discussing the fact that domestic breeds vary. This may seem pretty obvious to us, but it was an important set up for the idea that variation is common. Remember– no variation, no selection.

He also goes to pains to convince readers that domestic breeds (e.g., of pigeons) were all descended from a common ancestor. Again, this may seem obvious to us, but as he notes (p. 50), almost all breeders assumed that each breed was descended from a different wild ancestor. So, he is using these examples to establish common descent and branching.

Several important ideas already appear in the chapter:

1) Although he didn’t know how heredity works he knew it is crucial for his mechanism (p.33).

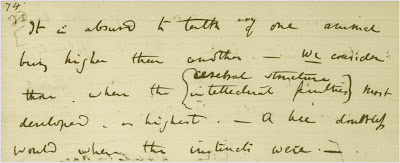

“Any variation which is not inherited is not important for us.”

2) Differences between modern organisms may be so great that it is difficult to imagine that they share common ancestors — he used the example of pigeons, which would be classified as different species if a taxonomist didn’t know they were domestic breeds because they look so different (p.44). And yet, all the information indicates that they are descended from the same ancestor species.

“Altogether at least a score of pigeons might be chosen, which if shown to an ornithologist, and he were told that they were wild birds, would certainly, I think, be ranked by him as well-defined species. Moreover, I do not believe that any ornithologist would place he English carrier, the short-faced tumbler, the runt, the barb, pouter, and fantail in the same genus”.

3) Selection is the main mechanism of change. Not crossing, not effects of environment, and so on (p.66).

“Over all these causes of Change I am convinced that the accumulative action of Selection, whether applied methodically and more quickly, or unconsciously and more slowly, but more efficiently, is by far the predominant Power.”

4) Selection is about the accumulation over many generations of almost imperceptibly slight changes (p.52-53). The emergence of breeds is gradual, probably too much to notice as it is occurring (p.62).

“We cannot suppose that all the breeds were suddenly produced as perfect and as useful as we now see them; indeed, in several cases, we know that this has not been their history. The key is man’s power of accumulative selection: nature gives successive variations; man adds them up in certain directions useful to him. In this sense he may be said to make for himself useful breeds.”

“But, in fact, a breed, like a dialect of a language, can hardly be said to have had a definite origin. A man preserves and breeds from an individual with some slight deviation of structure, or takes more care than usual in matching his best animals and thus improves them, and the improved individuals slowly spread in the immediate neighbourhood. But as yet they will hardly have a distinct name, and from being only slightly valued, their history will be disregarded. When further improved by the same slow and gradual process, they will spread more widely, and will get recognised as something distinct and valuable, and will then probably first receive a provincial name.

…

But the chance will be infinitely small of any record having been preserved of such slow, varying, and insensible changes.”

5) Selection is known to occur, at least with breeding (p.52, p.55).

“The great power of this principle of selection is not hypothetical.”

6) Most changes are ignored (neutral) or detrimental, but some are noticed and selected (p.61).

“Nor let it be thought that some great deviation of structure would be necessary to catch the fancier’s eye: he perceives extremely small differences, and it is in human nature to value any novelty, however slight, in one’s own possession. Nor must the value which would formerly be set on any slight differences in the individuals of the same species, be judged of by the value which would now be set on them, after several breeds have once fairly been established. Many slight differences might, and indeed do now, arise amongst pigeons, which are rejected as faults or deviations from the standard of perfection of each breed.”

7) Selection doesn’t require conscious effort. It can be unconscious (p.56).

“…a kind of Selection, which may be called Unconscious, and which results from every one trying to possess and breed from the best individual animals, is more important. Thus, a man who intends keeping pointers naturally tries to get as good dogs as he can, and afterwards breeds from his own best dogs, but he has no wish or expectation of permanently altering the breed.”

8) Large populations are best for selection (p.63).

“But as variations manifestly useful or pleasing to man appear only occasionally, the chance of their appearance will be much increased by a large number of individuals being kept; and hence this comes to be of the highest importance to success.

…

When the individuals of any species are scanty, all the individuals, whatever their quality may be, will generally be allowed to breed, and this will effectually prevent selection.”

9) If breeds are going to diverge, they must not interbreed (i.e., what we would now say means blocking gene flow) (p.64).

“In the case of animals with separate sexes, facility in preventing crosses is an important element of success in the formation of new races,—at least, in a country which is already stocked with other races. In this respect enclosure of the land plays a part.

…

On the other hand, cats, from their nocturnal rambling habits, cannot be matched, and, although so much valued by women and children, we hardly ever see a distinct breed kept up; such breeds as we do sometimes see are almost always imported from some other country, often from islands.”