The classic creationist argument regarding “irreducible complexity” is that many multi-part biological systems cannot function without all of their parts present together in the current configuration, and thus that there is no possibility that such systems evolved through gradual intermediates. In the past, the most common examples included features at the organ level such as eyes, but with the rise of intelligent design this has shifted to more esoteric cases like bacterial flagella, the immune system, and the blood clotting cascade.

The argument is false in any case, as it overlooks the commonplace occurrence of shifts in function in evolution, in which subsets of the current system still function, but in a different way. For example, one can remove large numbers of components from bacterial flagellar systems rendering it useless for locomotion, yet the structure still functions in secretion. The point is that such complex structures could evolve through functional intermediates, but that the functions of those intermediates may have been quite different from the function of the system as it is observed now.

In other cases, the concept of irreducible complexity is refuted by simply finding cases in particular species where one or more components are missing but the system still functions in the same capacity. Some bacteria exhibit only a subset of the flagellar components found in other species but still swim. Whales lack Factor XII (Hageman factor) but their blood still clots1 (and, in fact, blood in humans with Hageman factor deficiency also still clots, though more slowly). Plenty of species lack major components of eyes found in vertebrates and cephalopod molluscs, but they see to an extent sufficient for their niches.

Bombardier beetles represent another classic creationist example of irreducible complexity that supposedly would be totally non-functional if any of the numerous components were absent. These beetles employ a mixture of hydroquinone and hydrogen peroxide which, when catalyzed, generates a strongly exothermic reaction in which a hot, repellent liquid is ejected at predators. The argument is that without all of the components present together, the defence mechanism of bombardier beetles would be useless. A typical example is given in this video, which gives an interesting overview of the complex system before concluding that the system could not work without all of the parts. In the beetle shown in this video, the liquid is heated to the boiling point of water, can be aimed with some accuracy, and is released in a series of high-velocity pulses.

It should be noted at this point that there are about 500 bombardier beetle species, divided into several tribes within the ground beetles. These are generally classified into two groups, the brachinoids and the paussoids. It is not entirely clear whether these are monophyletic, meaning that they all evolved from a common ancestor, or whether bombardier-like defence mechanisms evolved independently at least twice. For the purposes of this discussion, the details of their relationships are not particularly relevant, and instead what matters is the diversity they now display. Most of what is known about bombardier beetles comes from studies of the brachinoids (e.g., Brachinus), but this reflects only a portion of bombardier beetle diversity.

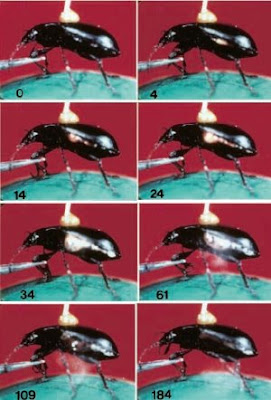

Metrius contractus is a species in the paussoid lineage that differs from other bombardier beetles in both lineages in important respects (Eisner et al. 2000). Notably, in this species the mixture of reagents is not ejected in a jet, it oozes out in a froth. M. contractus lacks the elytral flanges found in its relatives that allow it to direct the fluid forward in a jet. It does not aim the abdomen to direct the liquid, rather the excreted foam may be channeled anteriorly along grooves in the elytra (wing covers). The mixture continues to bubble after it is released, indicating that the reaction is not completed before being ejected and the solution is not boiling hot but is ejected at only about 55 degrees celcius. But the beetle survives.

(Eisner et al. 2000). Notably, in this species the mixture of reagents is not ejected in a jet, it oozes out in a froth. M. contractus lacks the elytral flanges found in its relatives that allow it to direct the fluid forward in a jet. It does not aim the abdomen to direct the liquid, rather the excreted foam may be channeled anteriorly along grooves in the elytra (wing covers). The mixture continues to bubble after it is released, indicating that the reaction is not completed before being ejected and the solution is not boiling hot but is ejected at only about 55 degrees celcius. But the beetle survives.

Crepidogaster ambraena and C. atrata are two African species of bombardier beetles in the brachinoid lineage but part of a tribe (Crepidogastrini) different from that of the brachinoids that have been studied in detail (Eisner et al. 2001). These species are similar to other brachinoids in morphological structure of the defensive system and in aiming the excretion by directing their abdomens at predators. However, they differ from the commonly described system in that their excretion is not boiling hot (about 64 degrees celcius), is more mist than jet, and is not pulsed when ejected. As a result, they are less effective than other brachinoids in terms of accuracy, the efficient ejection of liquid at high velocity, and repetitive cooling of the reaction chamber. In other words, slight changes in the structure or function of valves within the system would provide significant advantages, as they did in other brachinoids. And yet, this beetle survives as it is.

The beetles discussed above are all modern species, and none is suggested to be ancestral to any others. As such, these comparisons do not in themselves provide information on the historical sequence of changes in the evolution of the most complex bombardier beetle defences. However, the continued existence of some species lacking one or more of the features found in other species clearly refutes the argument that the complete system must arise all together in order to be functional. Much work remains to be done in sorting out how their remarkable features arose, but there is no reason to believe that they are not the product of gradual evolutionary change.

____________

Notes

1. It is worth pointing out that whales do have the gene for Factor XII but it is pseudogenized, and that the amino acid sequence of the protein it would produce is more similar to artiodactyls than to other mammals (Semba et al. 1998).

References

Eisner, T., D.J. Aneshansley, M. Eisner, A.B. Attygalle, D.W. Alsop, and J. Meinwald. 2000. Spray mechanism of the most primitive bombardier beetle (Metrius contractus). Journal of Experimental Biology 203: 1265-1275.

Eisner, T., D.J. Aneshansley, J. Yack, A.B. Attygalle, and M. Eisner. 2001. Spray mechanism of crepidogastrine bombardier beetles (Carabidae; Crepidogastrini). Chemoecology 11: 209-219.

Semba, U., Y. Shibuya, H. Okabe, and T. Yamamoto. 1998. Whale Hageman factor (Factor XII): prevented production due to pseudogene conversion. Thrombosis Research 90: 31-37.